By Iris Nelson, Quincy Public LibraryThe focus of this section on “Women at Work” will feature those women who boldly pioneered new working arenas, most of which had habitually been in the male domain. Women have always worked–but they did not have the opportunity to educate themselves, establish professional identities, and broaden the female experience to work outside the acceptable social norm. Evolving beyond the roles to which women had historically been relegated, those of the nineteenth century distinguished themselves as artisans and merchants in the business arena, as well as in the professions of education, law, and medicine.

Profound change occurred during the 1800’s–a new social order was born. Changes in the political, social, and cultural environment in the United States affected the prevailing ideologies. The American Revolution sounded a permanent prominence to the ideals of liberty and equality. Men and women were increasingly unwilling to tolerate the political and social injustices. This spark, combined with the advances of the Industrial Revolution that lessened the burdens of domesticity, slowly affected the cultural landscape.

Before the Civil War women’s groups were social in orientation; after the war women’s groups took on broader issues including the rights of women. Additionally, educational institutions slowly became co-educational. Land-grant colleges and women’s institutions were established to encourage women to earn college degrees and seek different avocations without threatening the contemporary role. Many women became schoolteachers. In 1870, the U. S. Census Bureau reported over 30,000 female proprietors in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio and Wisconsin. By 1880 growing numbers of Illinois businesswomen were active artisans working as milliners, dressmakers, bakers, and photographers. As merchants, such as grocers and dry goods shopkeepers, women pursued and successfully operated business establishments. Midwestern women in amazing numbers marketed their acquired domestic skills and were remarkably active in commercial ventures.

By the 1870’s, advanced professional degrees were attainable at some institutions of higher education. The 1880 Illinois Census indicates that there were 9 women lawyers and 155 women physicians. Slowly and in small numbers, women began to earn degrees in medicine and law as well as other professions.

In this section, we honor these women of unique distinction who sought worlds beyond the grasp of previous generations. Given opportunity and a choice of careers, women shed their previous societal confines and vigorously contributed to the workplace. The dynamics of the workplace was altered forever.

Murphy, Lucy Eldersveld. “Her Own Boss: Businesswomen and Separate Spheres in the Midwest, 1850-1880.” Illinois Historical Journal. 80 (1987): 155- 176.

Cora Agnes Benneson (1851-1919)

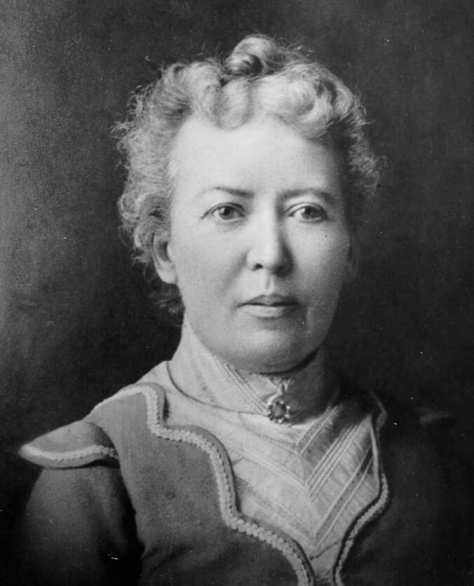

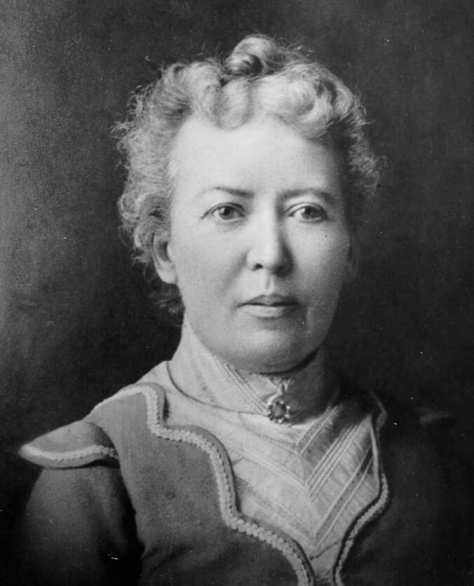

Cora Agnes Benneson, lawyer and writer, was born in Quincy, Illinois on June 10, 1851 to Robert S. and Electa Ann Benneson. Cora was the youngest of four daughters, attended college and law school, became one of the first women to practice law in New England, and traveled around the world to study legal procedures in other countries. Photographs and primary documents are courtesy of Mrs. Caroline Sexauer, Quincy, great niece of Cora.

|

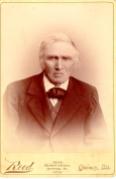

Cora Benneson

“Miss Benneson was an astute observer of the activities of women. She gave voice to the opinion that ‘the coming woman will not hesitate to do whatever she feels will benefit humanity, and she will develop her own faculties to the utmost because by so doing she can best serve’.” |

|

Cora Benneson, age 18, Aug 1869

At the University of Michigan Law School, Cora was one of two women in a class of 175. She was admitted to the Michigan and Illinois bars in 1880. At an early age Cora displayed an unusual ability in getting at the core of an argument, according to Mary Esther Trueblood. |

|

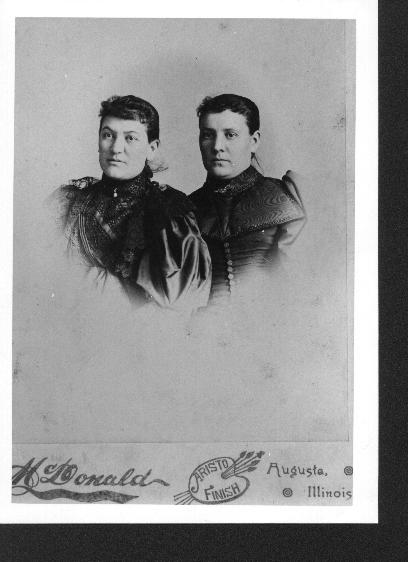

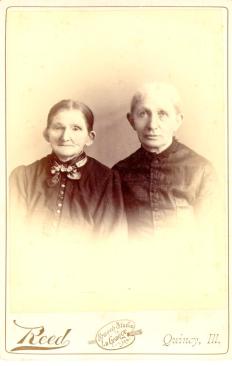

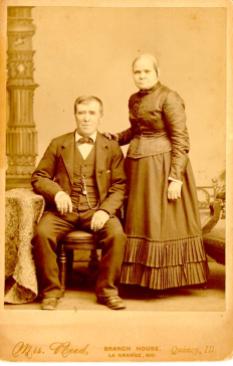

Sisters Cora & Lina Benneson

All four sisters were tutored by their mother, Electa Ann Parks Benneson, a former teacher. Cora was an eager student. Miss Trueblood states that “at twelve she was reading Latin at sight, had acquaintance with much of the best literature, and was industriously collecting and tabulating historical facts.” |

|

[l to r] Alice Bull, Mary Marsh, Nellie Marsh, Cora Benneson

Graduating class from the Quincy Seminary or Miss Chapin’s Private School, as it was commonly known. The Quincy Seminary was in existence from 1867-1876. |

|

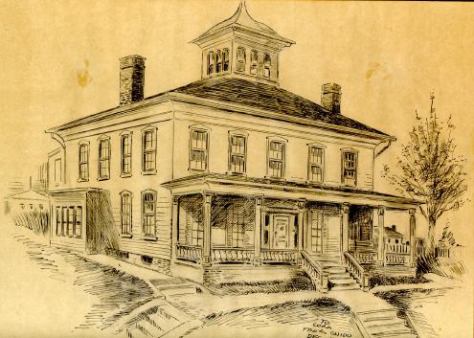

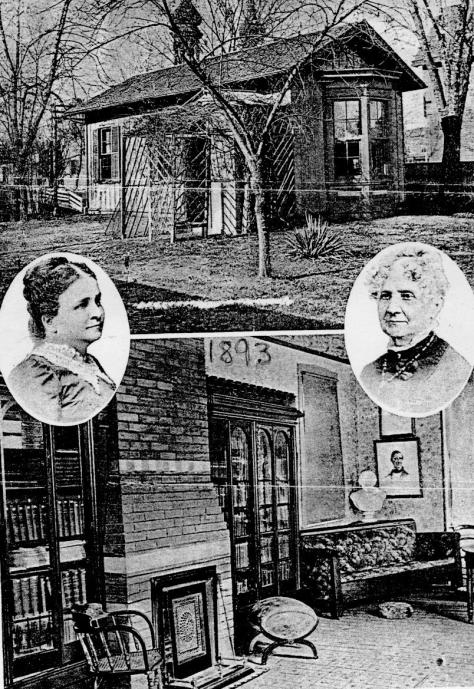

Childhood home of Cora Benneson, 214 Jersey, Quincy, Illinois

The homestead of the Bennesons was a large mansion located on the bluffs of the Mississippi River at 214 Jersey Street. The home, situated above a series of terraces, commanded a magnificent view of fourteen miles of the river. |

|

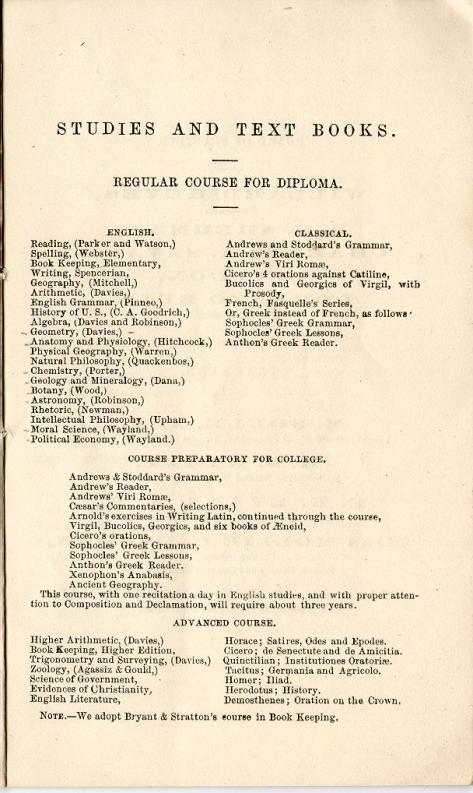

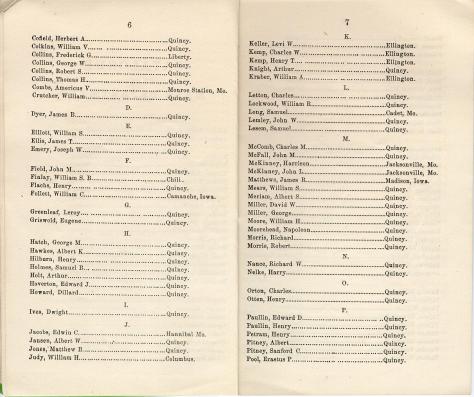

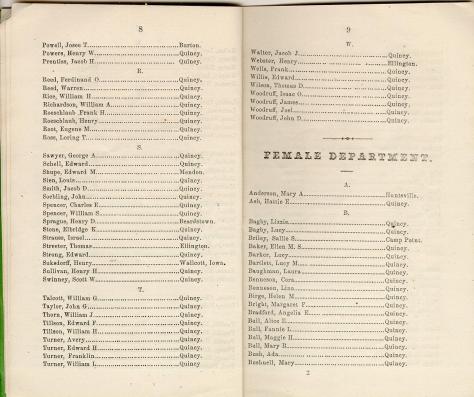

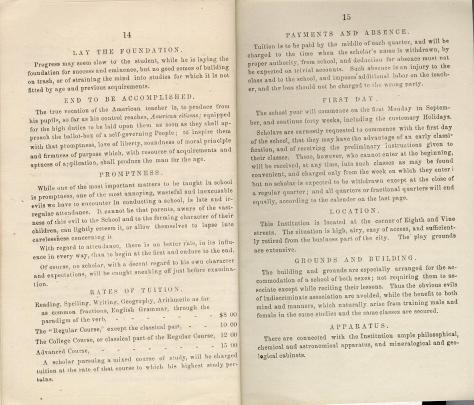

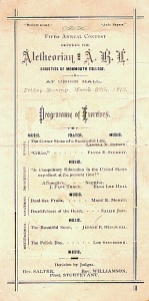

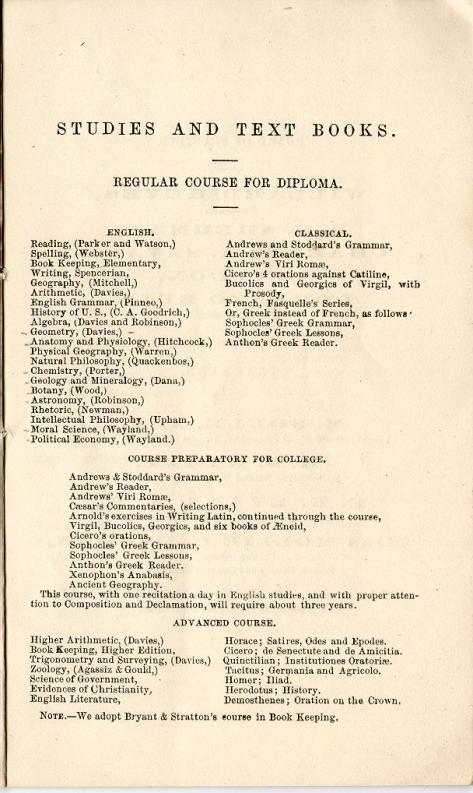

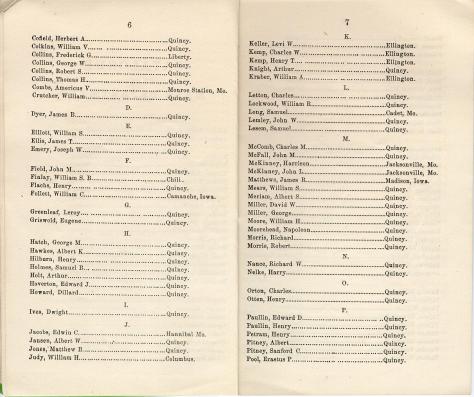

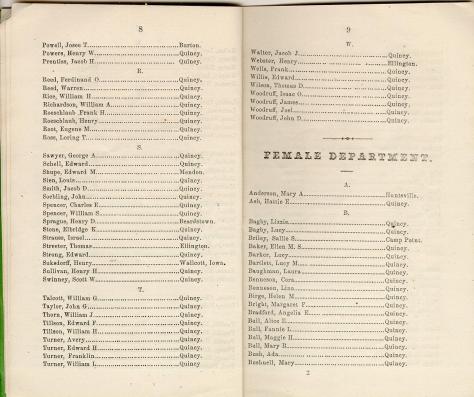

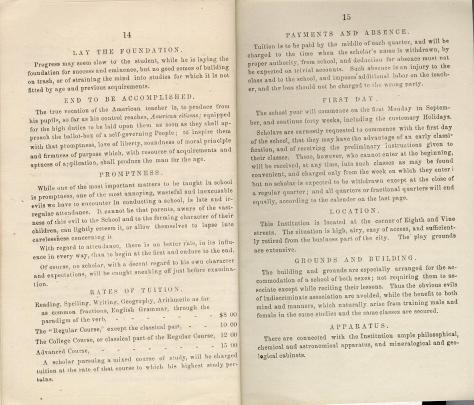

Quincy Academy Booklet, 1864-65

At age 15, Cora finished the course of study at the Quincy Academy, the equivalent of a good high school. The 5 x 7 inch original booklet contains a list of studies and text books as well as policies of the school. [Complete Booklet] |

|

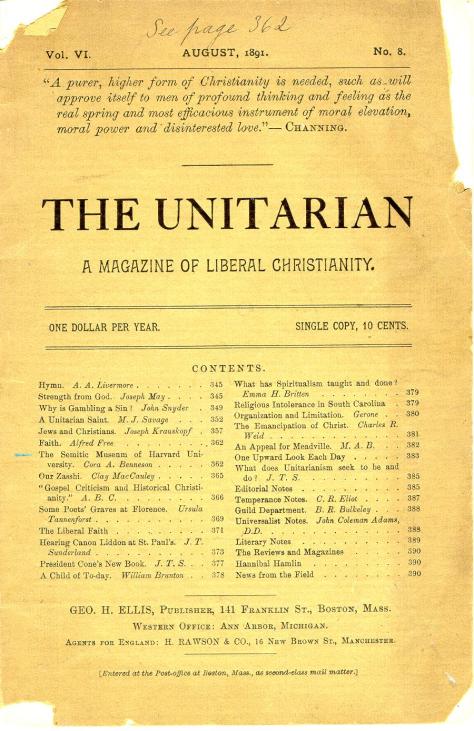

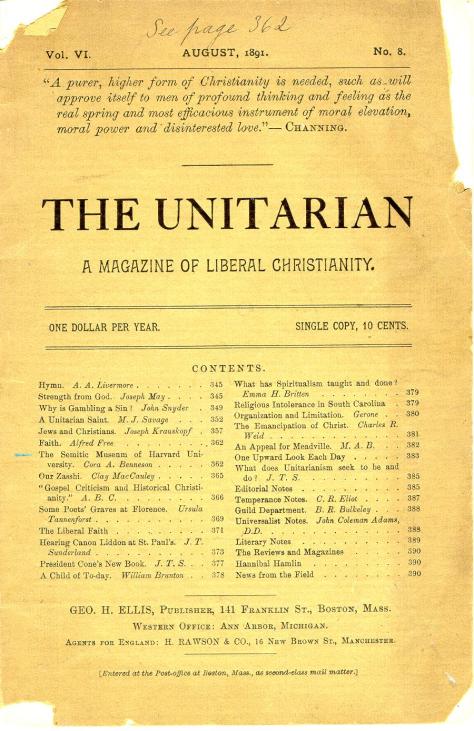

Magazine Article by Cora Benneson. “The Semitic Museum of Harvard University.” The Unitarian August, 1891: 362-365.

Cora was a noted writer and wrote extensively on a variety of topics including education, politics, and the social sciences. She became a recognized authority on government and presented papers at various association meetings. |

|

Reprint of 1904 article entitled “Representative Women of New England” by Miss Mary Esther Trueblood. [Complete Article]

Miss Trueblood states that Cora “had scholarly instincts, rare literary taste, and constantly took up new studies.” |

|

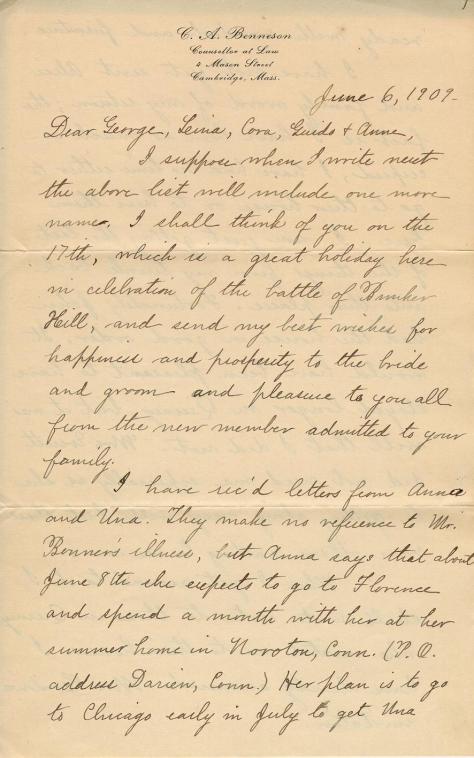

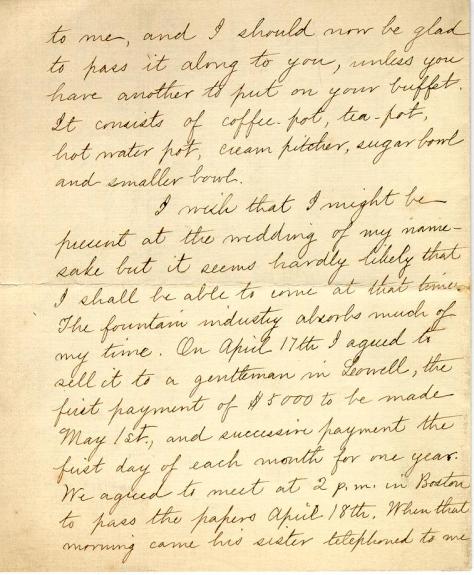

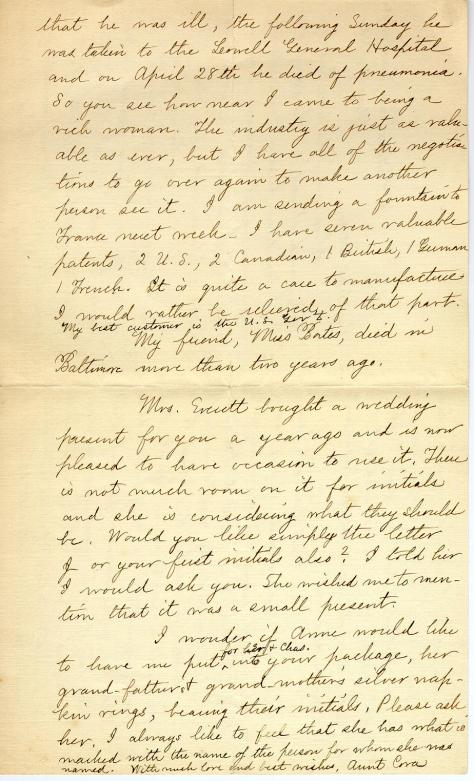

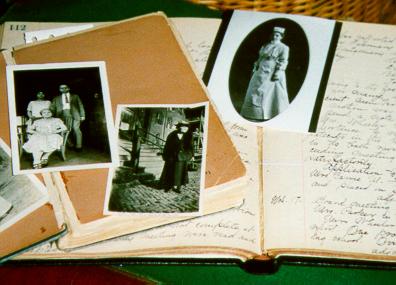

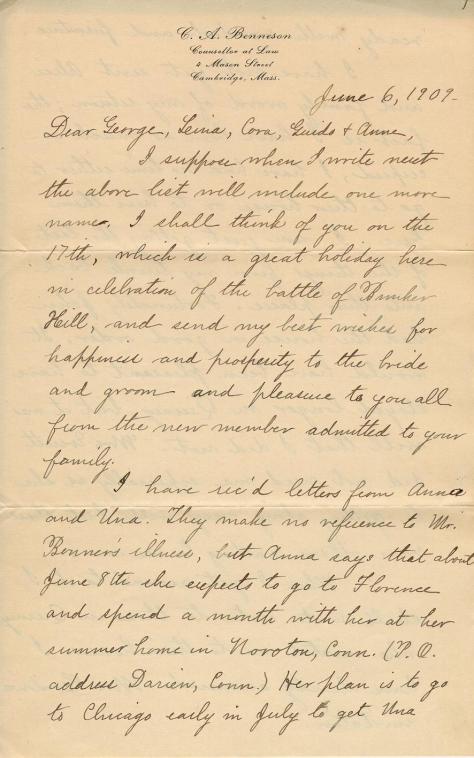

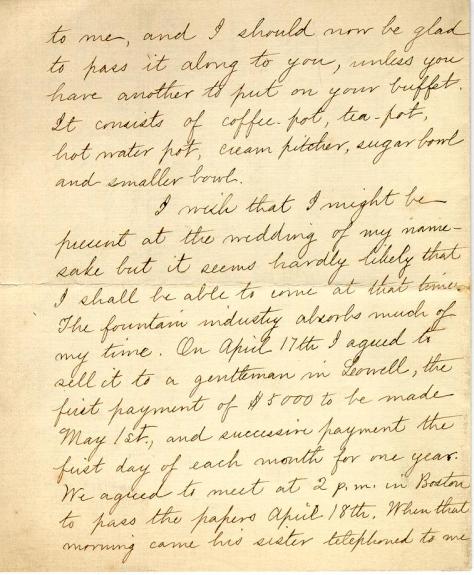

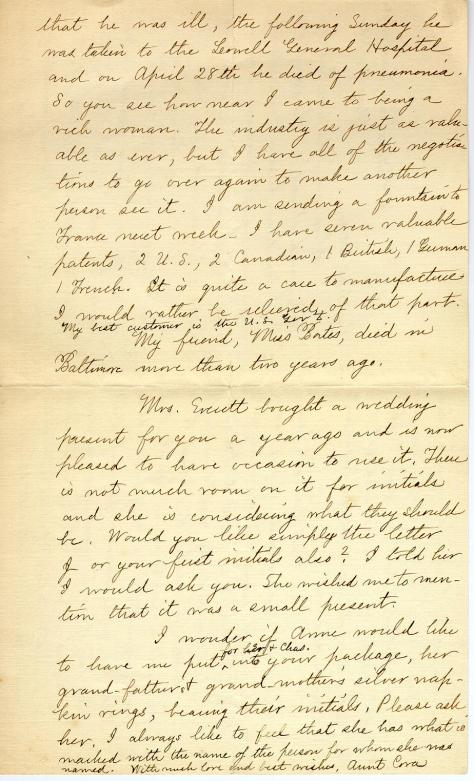

Letter from Cora to her family in Quincy, June 6, 1909. [Complete letter] |

|

Letter from Cora, May 12, 1912. [Complete letter] |

|

Pioneer Women of Quincy: Cora Benneson predicted modern woman would develop own faculties by Helen Warning |

Cora Agnes Benneson

Source: Quincy Herald Whig Newspaper, February 20, 1977

Series Title: Pioneer women of Quincy

[headline] Cora Benneson predicted modern woman would develop own faculties

By Helen Warning

Reprinted with permission from The Quincy Herald-Whig and from Helen Warning. Photographs are courtesy of Mrs. Caroline Sexauer, Quincy, great niece of Cora.

“The coming woman will not hesitate to do whatever she feels will benefit humanity, and she will develop her own faculties to the utmost because by so doing she can best serve.”

“She will have a home, of course. She will not marry, however, for the sake of a home, because she will be self-supporting. The home she will help to found will not be for the selfish gratification of two individuals but a center of light and harmony to all that come within the sphere of its radiance.”

“Many so called duties that drain the nerve force of the modern women, the coming woman will omit or delegate. One duty she will not delegate-the character moulding of her children. The woman of the future comes not to destroy, but to fulfill the law. She will not confine her influence to a limited circle. It will be felt in the nation’s housekeeping. Wherever she is needed, there she will be found.”

Such oration may be anticipated from today’s liberated woman but not from one who lived primarily in the 19th century and was of midwestern background. Yet that far sighted knowledge was espoused by Quincyan Cora Agnes Benneson, who was born here in 1851.

Cora Benneson’s youth fell at a period when women were becoming active forces in society, which explains her farsightedness. It was a period when colleges and universities were being opened to women as well as men. Girls were beginning to study, not because it was fashion, but because they were impelled by an awakening of consciousness.

Miss Benneson’s parents, prominent Quincyans who shared identical interests whether educational, religious or philanthropic, promoted her early inclination to philosophic studies. They entertained in their home many men of note, of whom Alcott and Emerson especially made a great impression on Miss Benneson.

Her father, Robert Smith Benneson, a native of Newark, Del., went to Philadelphia and thence to Quincy in 1837, where he became prominently identified with the business and municipal affairs of the city. He was organizer and director of various corporations, promoter of the original act levying taxes for school purposes in Illinois, president of the Quincy Board of Education for 14 years, and a long time, one of its members, alderman for two terms and mayor during the Civil War. During this crisis, he saved the credit of the city by giving his personal notes to meet its obligations.

The family represented the best traditions of New England through the mother, Electa Ann Park Benneson, a direct descendant of Richard Park, one of the first settlers of Cambridge, Mass. Called “Annie Park” as a young woman, Mrs. Benneson taught school a few years in Brighton, Mass. and while visiting in Quincy met Robert Benneson.

The Bennesons helped to establish the Unitarian Church and for many years, Mrs. Benneson was superintendent of the Sunday school. The keynote of her teaching was “Do right because it is right.”

Her activity was not confined to the home and church, however. “Any movement aiming at the good of the community found her a ready helper,” according to Mary Esther Trueblood in “Representative Women of New England.” She was interested in Woodland Home, an asylum for orphans and friendless, and united all the churches of Quincy in a fair for its benefit. During the Civil War, she devoted herself to soldier’s families and to the wounded in the hospitals.

“Her feelings found expression in deeds of kindness rather than words. She had scholarly instincts, rare literary taste and constantly took up new studies,” according to Miss Trueblood.

Cora Benneson, the youngest of four sisters, she inherited her father’s physique and her mother’s mental characteristics. A sturdy child, Miss Benneson was orderly, accurate, self-reliant, ambitious, and persevering according to Miss Trueblood.

Her mother, who tutored all her children, soon perceived that the wisest way to direct her was to answer her questions exactly and fully and to explain to her principles and the relation of things.

She and her sisters edited a magazine called, “The Experiment,” which was read aloud every week in the family circle and contained Cora’s first writings. At age eight, she wrote a satire on a fashionable woman’s call, “A Visit,” which won the prize her mother had offered that week. At nine, at her request, her father allowed her to help keep his books. When 12, she was reading Latin at sight and had an acquaintance with some of the best literature. She early displayed an unusual ability in getting at the pitch of the argument and in summing up a conversation in a few words of her own, a trait so necessary in her chosen profession of counselor-at-law and special commissioner.

As a youngster sitting in church with paper and pencil, she drew trees as she listened to the discourses. The trunk represented the text, or main thought, the branches the ideas leading from it. In her judgement, the merits of a sermon depended upon whether or not it could be “treed.”

In school, she really excelled other children her age. At age 15, she had finished the course at the Quincy Academy, the equivalent of a good high school, and at 18 years she was graduated from the Quincy Seminary. From then until she entered college, she had a full social life.

The Benneson home, located at 214 Jersey, was a large mansion situated above a series of terraces and surrounded by trees and shrubs. Its location provided a view of 14 miles of the Mississippi River. Miss Benneson, a good rower, knew every inlet and island of the Mississippi and as a child watched steamers going to and from St. Louis and St. Paul with untiring interest. The Mississippi, it is said, was her unconscious friend, helping her to think and act.

The Benneson home, located at 214 Jersey, was a large mansion situated above a series of terraces and surrounded by trees and shrubs. Its location provided a view of 14 miles of the Mississippi River. Miss Benneson, a good rower, knew every inlet and island of the Mississippi and as a child watched steamers going to and from St. Louis and St. Paul with untiring interest. The Mississippi, it is said, was her unconscious friend, helping her to think and act.

The home was later located on Broadway between Fifth and Sixth, next door to the F. T. Hill home. The house was torn down to provide additional grounds for the detention home that stood at the site until the building of the Lampe Hi-Rise a few years ago.

Miss Benneson’s ambition for a higher education led to her entrance at the University of Michigan in 1875, only five years after women students were first admitted. She completed the four year course in three and was graduated in 1878 with an A. B. degree. Her first public appearance at the university was a debate during her freshman year which she won. During her senior year, she was editor of “The Chronicle,” the leading college newspaper at the time. She was the first woman to fill the position.

Her application for admission to the Law School of Harvard University, signed by five Harvard alumni, was refused on the grounds that the equipment at the university was too limited to make suitable provision for receiving women.

She returned to the University of Michigan and was one of the two women in a class of 175 law students. Miss Benneson felt no prejudice from her male counterparts, was elected secretary of the class, was presiding officer in the debating society and judge of the Illinois Moot Court.

She received her L. L. B. degree in 1880 and her A. M. degree in 1883. After being admitted to the Michigan and Illinois bars in 1880, she took a two year, four month round-the-world trip.

Starting in San Francisco, she traveled westward, stopping in Hawaii, Japan, China, Burma, India, Arabia, Abyssinia (Ethiopia), Egypt, Palestine, Turkey and all the principal countries of Europe. She studied the costumes, manners, and laws of many of the nations she visited and a series of letters, which she wrote home, were copied by her father and are now in the collection of a great-niece, Mrs. William (Caroline) Sexauer. The contents reveal her findings.

“War seems imminent,” she wrote from Canton, China, Christmas night 1883, “and there has been one engagement. This creates in the Chinese a strong anti-foreign feeling, in which the mass of the people, make no distinction between English, French, and German. The Chinese word for foreigners is literally translated, White Devils. We therefore thought it best to telegraph Mr. Damon when we would leave Hong Kong, feeling sure that he would not let us come if it were unsafe.” The Chinese at the time were anti-French.

From the Pearl River, Dec. 27, 1883, she wrote, “While I feel that the position of the American woman is not yet exactly what it should be and what I hope it may sometime be, still in traveling in Oriental countries one realizes that in our own we have much to be very very thankful for.”

From Calcutta, Jan. 21, 1884, she wrote, “The Burmese are fond of high colors, especially in their turbans, and red is very becoming to their dark skins. The women wear nose rings and many ear rings. Also bangles on their wrists and ankles. They put their money into jewelry and carry it on their persons, instead of depositing it in banks. They are a slender, frail-looking people.”

In her mideast travels, Miss Benneson noted the places where she stopped with the passages where they are mentioned in the Bible.

Her April, 1884, letter from Jerusalem noted she entered Jerusalem on the evening of the Passover. “Many of the Jewish houses were brilliantly lighted. Our diligence stopped just outside the gate and we entered on foot. You see no carriages in Jerusalem. The streets are too narrow.” Miss Benneson found traveling in Palestine more expensive than elsewhere.

From Athens, Greece, May 20, 1884, she wrote she hoped to write a closer account of what she was seeing now that she had left the half-civilized races behind and entered Europe, where the distances were shorter and traveling facilities better.

Miss Benneson had the distinction of being one of the few that had visited the law courts of all the principal civilized countries as well as their chief governing assemblies.

Upon her return home, Miss Benneson lectured on her travels in Quincy, Minneapolis, St. Paul, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, Boston and other cities and her programs were well attended.

She edited for a time the “Law Reports” of the West Publishing Co. in St. Paul and during 1887-88 held a fellowship in history at Bryn Mawr College. Moving to Cambridge, Mass., she made that city her permanent residence and in 1894 was admitted to the Massachusetts bar. She was appointed special commissioner by Gov. Greenhalge in 1895, had the appointment renewed in 1905 and held the position until her death.

One of the first women to enter the practice of law in New England, Miss Benneson found no antagonism among her fellow lawyers and gradually acquired a large and successful practice.

A recognized authority on government, her 1898 paper, “Executive Discretion in the United States,” and her 1899 paper, “Federal Guarantees For Maintaining Republican Government in the States,” were both read before the American Association for Advancement of Science and resulted in her election as a fellow in the society in 1899. In 1900, she was elected secretary of the social and economics section of the association.

Another paper, “The Power of Our Courts to Interpret the Constitution,” read before the association, led to the announcement of a book dealing with the same general subject. Several other papers followed.

In June, 1899, she gave the Alumni Poem at the University of Michigan commencement and in 1903 read the Ode of her class at its anniversary meeting.

Miss Benneson was not indifferent to any human interest and was a keen observer of all the activities of women, according to Miss Trueblood. She was quick to deplore any tendency that would destroy womanliness in the highest sense. She was ready to aid any movement that would give women a fuller and richer life and them more efficient members of society. She believed that reforms cannot be forced upon society, but must come through a natural evolution and that one can do another no more serious injury than to deprive him of liberty of opinion and action.

An honorary member of the Illinois State Historical Society, she gave an address at the 1909 annual meeting of the association entitled, “The Quartermaster’s Department in Illinois 1861-62.” She was among the early members of the Friends in Council and was founder of the original Unity Club of the Unitarian Church, for many years a forum where the brightest men and women of the city discussed the leading topics of the day. She was a member of the Unitarian Church.

About a year before her death, which occurred in Boston on June 8, 1919, Miss Benneson gave up her active practice of law and prepared herself as a civics teacher under the auspices of the state board of education of Massachusetts, which had established a school in Boston for the Americanization of foreigners. According to her obituary, Miss Benneson worked so hard to prepare herself for this new work that she suffered a breakdown in health and her labors were the cause of her death. The diploma entitling her to the position which she sought arrived just a day after she died.

In addition to Mrs. Sexauer, Miss Benneson is survived by two great-nephews, Charles Seger of Quincy and Benneson James of Maryville, Tenn. And a great-niece, Mrs. Charles Higgins of Memphis, Tenn.

[More information about Cora Benneson.]

Contributing Library:

Quincy Public Library, Quincy, Illinois

OBITUARY OF MISS CORA BENNESON

From: Quincy Daily Herald Newspaper, June 12, 1919.

BRILLIANT WOMAN DIES. . .

MISS CORA BENNESON WAS NATIVE OF QUINCY.

Member of Bar of Three States and Had Won Many Honors-Founder of Unity Club in This City.

Miss Cora Benneson, one of the women who has made the name of Quincy known abroad, and at one time one of the city’s best known residents, died at her home in Cambridge, Mass., last Sunday and was buried in Mt. Auburn cemetery. Word of her death came to her sister, Mrs. George Janes of this city. Miss Benneson was one of the few women attorneys in the country, and for many years had been practicing her profession in Boston. About a year ago she gave up her active practice of the law, and fitted herself as a teacher of civics under the auspices of the state board of education of Massachusetts, which has established a school in Boston for the Americanization of foreigners. Miss Benneson worked so hard to fit herself for this new work that she suffered a break down in health about six weeks ago, and her labors were the cause of her death. Her diploma, entitling her to the position which she sought, came just a day after she died.

WON MANY HONORS

Miss Benneson was born in Quincy, the daughter of Robert S. and Electa Ann Benneson. She was graduated from Miss Chapin’s School, and later attended the University of Michigan, where she received her L. L. B. degree in 1880, and her A. M. degree in 1883. She was admitted to the Michigan and Illinois bars in 1880 and to the Massachusetts bar in 1894.

In [1883], Miss Benneson left Quincy for a tour of the world, which lasted for two years. On her return she went to St. Paul [Minnesota], where she edited law reports for the West Publishing Company. She gave lectures on her trip around the world in 1885-86, and was appointed a special commissioner in Massachusetts in 1895, and subsequent years. She was awarded a fellowship in history at Bryn Mawr College in 1887. She was also an honorary member of the Illinois State Historical society, and sole trustee of the Edward Everett estate in Boston.

FOUNDER OF UNITY CLUB

Miss Benneson was a contributor to journals on topics of law, education, and political and social science, and throughout the east was recognized as one of the leading members of the bar. In Quincy she was prominent in the literary life of the city, and was one of the early members of Friends in Council and the founder of the original Unity Club of the Unitarian Church. Robert S. Benneson, her father, was one of the first mayors of Quincy and the family was a prominent one. The old family home was at 214 Jersey Street, and afterward on Broadway, between Fifth and Sixth, next door to the F. T. Hill home. The house was torn down to provide additional grounds for the present detention home.

Miss Benneson leaves two sisters, besides Mrs. Janes. They are Mrs. Anna McMahon, now at Atlantic City, N.J. and Mrs. Alice B. Farwell of Boston. Guido Janes, Mrs. Charles Seger and Mrs. Philip Schlagenhauf of this city, are nephew and nieces of Miss Benneson.

Bibliography:

- “Cora Agnes Benneson, 1851-1919.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society XII (1919): 307-309.

- Trueblood, Mary Esther. Cora Agnes Benneson Boston: Geo. H. Ellis Co., 1904.

Contributing Library:

Quincy Public Library, Quincy, Illinois

Nellie Kedzie Project

Click on an image to see a larger image.

Portrait of Nellie Sawyer Kedzie, 1901 polyscope photo

An early foods laboratory, 1930s. Cooking was one of the subjects taught to the small number of female students at the Domestic Science department, created in 1897, the number gradually increasing over the next few years. Most parents were reluctant to send their daughters to an institute of higher education were it not for the homemaking skills offered.

During the World Wars, students in the Home Economics Club becamse involved in fund-raising and leadership organizations. Women had a chance to leave the household and be exposed to female role models who had achieved success.

In food laboratories, many types of stoves were used: coal, gas, kerosene, and electric attachments, among others. A large stove was placed at one side of the room, and smaller individual stoves near a worktable for each student or for pairs.

A sewing classroom. Students were offered courses in Costume Design, Textiles and Laces, added in the early 1920s. Laundry was also taught, emphasizing the chemistry of hot and cold water, soaps, and removal of stains and oil.

Besides cooking, students learned the chemistry of food, food principles and classification, as well as food marketing. One of the courses’ prerequisites was Physics and Botany. Students spent 4-6 years to complete their major’s requirements.

The Home Economics department suffered most from the 1963 fire in Bradley Hall. Most of Lydia Bradley’s treasures that she had given to the Department were burned and lost. The Department was re-developed, new courses added to meet the requirements for the American Dietetic Association in 1967. Such courses included Nutrition, Diet and Disease, and Consumer Education.

Dorothy Holmes, great grand-niece of Lydia Moss Bradley, weaving on the loom in the Home Economics department at the Bradley Polytechnic Institute, in 1937.

Nellie Sawyer Kedzie Jones

When Lydia Moss Bradley decided to found Bradley Polytechnic Institute as an institution for the education of both young men and young women, she became destined to cross the path of another influential woman: Nellie Sawyer Kedzie Jones. Whether Mrs. Bradley tried to pursue Mrs. Kedzie to come to Bradley or whether their association was a fortuitous accident, we don’t know. What we do know, is that Nellie Kedzie was a pioneer in the field of Domestic Economy, and that her few years at Bradley seem to have had a profound impact on both the institution as well as her own career. The following is a long excerpt from Dr. Nina Collins’ Book: An Industrious and Useful Life: The History of Home Economics at Bradley University. [United States]: n.p., 1994.

Mrs. Nellie Sawyer Kedzie came to the new Bradley Polytechnic Institute in 1897 to become an assistant professor, and head of the newly developing Domestic Economy Department. She had graduated with the Bachelor of Science degree from the Kansas Agricultural College. Mrs. Kedzie was listed as the third faculty member in order of priority in the board of Trustees records. Hoeflin in History of a College: from Woman’s Course to Home Economics to Human Ecology offers some insight into Nellie Kedzie:

A radical change occurred in 1882 when Mrs. Nellie S. Kedzie, a very young graduate of the college, who had earned a B.S. in 1876 and a M.S. in 1878 but had no special preparation for the work, was put in charge to succeed Mrs. Mary Cripps. Mrs. Kedzie was a young widow living with her parents in Topeka. She had married Robert R. Kedzie as the culmination of a courtship which began when Professor Kedzie had taught chemistry at the college during the absence of his brother, William K. Kedzie, who went on leave to Europe to study the types of chemistry laboratories. At Christmas time of 1881 Robert came from Mississippi Agricultural College, where he was professor of Chemistry, to marry Nellie Sawyer. They returned to Mississippi, where he died seven weeks later. Upset by his death, Nellie Kedzie then moved back to her parents’ home in Topeka. (p. 14)

How Mrs. Kedzie became a leader in the newly developing field of domestic science/home economics was a story told be Nellie Kedzie herself, on her 86th birthday, to the Kansas State Alumni Newsletter, the K-Stater, in an article of October 1954 entitled “Pioneering in Home Economics.”

President Fairchild of KSAC, who was calling on alumnae of the College, called on her in the summer of 1881. She invited him to eat supper with her with her family. At the end of the meal, the president said to her, “Do you think you can teach Kansas girls to make such biscuits as these we have been eating?” Her surprise answer to the surprise question was “I can try.” That fall she went to KSAC to try to help college girls to become efficient homemakers with less effort than many women were exerting.” (ibid, p. 14)

The socially acceptable overt agenda of teaching young women to become better homemakers in the setting of higher education was obviously operating here. Even the development of the curriculum would need “manly help,” which would of course, give more credibility to the project of educating young women in colleges. Nellie Kedzie (Jones) remembered:

“The Regents and the President helped me make a list of what knowledge might be valuable to girls. We believed that every girl ought to have some knowledge of hygiene to keep herself in the best of health. Also, that she should be thinking of what foods she will want to learn to cook and serve to a family and she should be able to make garments needed by herself and by anybody dependent upon her.” And according to Mrs. Kedzie Jones, that is the way that the program to teach hygiene, sewing, and cooking was decided. (ibid, p. 14)

Most scholars would place Kansas (state university) among the pioneers in the development of home economics. As a pioneer in the discipline, Mrs. Kedzie was faced not only with developing a curriculum and appropriate textbooks, but also with the development of a philosophy of this new discipline. Mrs. Kedzie, in speaking about this challenge, stated:

“The main goal was to elevate home standards and to lessen labor, the constant quest to discover an easier way” . . . . Until 1884 Mrs. Kedzie was the only woman on the faculty . . . . In 1887, Mrs. Kedzie was given the rank of professor, the first woman to hold that title at KSAC . . . . Handwritten notes dated October, 1889, of Mrs. Nellie Kedzie . . . . discussed how few women in history had assumed positions of leadership. She wrote that most were like her mother and grandmother who had been pioneers and had to struggle hard to keep their homes going . . . . Because of the personal work of Mrs. Kedzie the legislature appropriated $16,000 in 1897 to erect Domestic Science Hall . . . . In 1902, Domestic Science Hall was renamed Kedzie Hall in honor of Mrs. Nellie Sawyer Kedzie (Jones), former professor of Domestic Science and head of the department, in recognition of her early work in organizing the field of home economics. It is believed that this is the first home economics building in the nation and the world that was named for a woman . . . .” (ibid, p. 16)

Bradley was able to secure the services of Mrs. Nellie Kedzie because of disastrous events at Kansas State University.

In 1897, radical changes were made in courses and the administration at KSAC. All of the faculty were asked to resign. Later when some were given the opportunity to return, neither Mrs. Nellie Kedzie nor Mrs. Winchip [who was to come to Bradley in 1898] chose to remain . . . . For the next five years after Mrs. Kedzie left, the Department of Domestic Economy was in a most unsettled condition. (ibid, p. 16)

Mrs. Kedzie must have felt some vindication after the naming of the first building in domestic science in her honor. She receives another great honor when she returned to Kansas for a special event. In 1925 at the golden anniversary celebration of the beginning of home economics at Kansas State, Mrs. Kedzie (Jones), who was at that time the State Leader of Home Economics Extension in Wisconsin, became one of the first three women to ever receive an honorary degree from KSAC — a Doctor of Law. (ibid, p. 29)

Nellie Kedzie was obviously a very persuasive and socially adept woman. Not only was she able to persuade the Kansas legislature to build a building exclusively for domestic science at that university, but she demanded and expected the very best in equipment and curriculum at the newly developing Bradley Polytechnic Institute.

***************The early curriculum [at Bradley] was most surely shaped by Mrs. Kedzie, Mrs. Coburn and Mrs. Feuling, all of whom had had full administrative experience in land grant universities, with a founder’s perspective. Their experiences were important as part of the contributions they made in shaping early curricula. These three women were well-traveled and had an excellent sense of the overt, societal-accepted agenda; as the early curriculum clearly states, a young BPI domestic science student would surely become a skilled homemaker. On the other hand, as is apparent in early course descriptions, textbooks used and recruitment material for domestic science, the subversive agenda of teaching of teaching women science, technology and mathematics was very important to these early leaders.

***************Certainly Nellie Kedzie and the curriculum she had shaped at Kansas State before coming to Bradley had an important part to play in the shaping of the early curriculum. According to Virginia Railsback Gunn, in Educating Strong Womanly Women: Kansas Shapes the Western Home Economics Movement, 1860-1914, Kansas State adopted the “manual-training approach to education in 1873, offer[ing] all students a program emphasizing a balance between sciences, general culture subjects, and technical courses, called industrials. . . .designed to prepare both males and females for paid vocations”(p.iii). Mrs. Kedzie must have felt most comfortable with the philosophy of Bradley Polytechnic Institute and Mrs. Bradley’s reason for the founding of the institute.

***************Teaching young women to be skilled in housework was certainly acceptable to most of society, which believed that doing housework would keep women “in their place.” Nevertheless, the subversive agenda is working here. The study of chemistry, sanitation and geometry, as part of the discipline that supposedly offered only training in housework, allowed young women to become educated, with their families’ blessing, in a field that was acceptable by almost all of society.

***************Bradley has always taken seriously its obligation to serve the central Illinois community. Holding “open houses” was one of those services from the very beginning. The availability to the community of what was being taught to women at BPI shows that the curriculum was, at least subtly, making its way into the mainstream of society. Education was not corrupting young women at BPI, but was improving everyone’s life by providing better managed homes. That women were being educated was not as newsworthy. Evidence of the delight of the press and the community in visiting the Institute can be found in early newspaper reports. According to the Herald, June 17, 1899:

6,000 people visited Bradley Institute last night and acquainted themselves with the workings of Peoria’s young but famous educational institution. They saw four hundred students busied with their varied tasks; young men and women representing every state in the union, who have an aim in life and who are taking advantage of the rare chances there offered to prepare them for a successful strife in their various callings. . . .But of all attractive places, the cooking laboratory certainly took first place. The savory odors from the dishes being prepared permeated the hallways and pulled at visitors like a magnet. This is more properly known as the department of domestic economy and is under the supervision of Mrs. Kedzie. The young ladies who were giving exhibitions in cooking wore pretty white dresses and sweet smiles. They gave the visitors tastes of their cookery and the room was packed at all times. All were loath to leave and others were clamoring for admittance.

More information on Nellie Sawyer Kedzie Jones can be found in the Special Collections Center of the Bradley University Library, Peoria, Illinois.

Contributing Library:

Cullom-Davis Library, Bradley University, Peoria, Illinois

Vivian Harsh (1890-1960)

Vivian Harsh was the Chicago Public Library’s first African American librarian. Under her direction, the Midwest’s largest collection relating to African American history was developed.

Vivian Harsh was a native of Chicago, born in 1890. At age 19, Harsh began working for the Chicago Public Library. By 1924, Harsh was the Library’s first black librarian. In 1932, the Library opened a new branch called the George Cleveland Hall Branch to serve the expanding south side black community. Vivian Harsh became the first head librarian of this new branch, and as such became the first African American woman to head a branch of the Chicago Public Library.

In her position as head of the new branch, Harsh gathered books, pamphlets and other documents about black history. Many African American writers, such as Richard Wright and Langston Hughes, donated books, manuscripts, and research to her rapidly growing collection. By Vivian’s death in 1960, the Vivian G. Harsh Collection of Afro-American History and Literature contained more than 70,000 volumes. The Collection, the largest of its kind in the Midwest, continues to be available to researchers today at the Carter G. Woodson Regional Library on South Halsted in Chicago.

Bibliography

- http://www.chipublib.org/002branches/woodson/wnharsh.html

Annie Turnbo Malone (1869-1957)

Annie Turnbo Malone achieved great success as a business woman. She is also remembered as a generous philanthropist.

Annie Turnbo was born in 1869 in Metropolis, near the far southern tip of Illinois. As a young woman, Annie developed hair care products which she sold door-to-door through the African American community of Lovejoy (now called Brooklyn), Illinois. In 1902, Annie moved her business to St. Louis. The 1904 World’s Fair was held in St. Louis and Annie’s business grew. She trained agents nationwide and began marketing her products under the name “Poro”, a name which she copyrighted. One of Annie’s agents was Madame C. J. Walker. Walker, often shares with Annie Turnbo the title the United States’ first African American millionairess.

Annie built a factory and a beauty-training school in St. Louis that she named Poro College. The factory and the school employed and educated many African Americans. Later, Annie moved the factory to Chicago. By the 1920s, Annie Malone was a millionaire. She shared her wealth with many less fortunate than herself. For example, she served as the President and donated fund for the construction of the St. Louis Colored Orphan’s Home, now known as the Annie Malone Children and Family Service Center. She also donated large sums of money to schools and colleges for African Americans and supported many students.

Bibliography

- Smith, Jessie Carney, Ed. (1992) “Annie Turnbo Malone” in Notable Black American Women. Gale Research Inc, Detroit, Michigan., Pp. 724-726.

Louisa McCall

Portrait of Louisa McCall, from Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois and History of Fulton County |

Photo of First National Bank of Canton, Illinois Photo of First National Bank of Canton, Illinois |

Louisa McCall has the unique distinction of being the first lady bank director in the United States. She assumed the position at the First National Bank of Canton in 1877 and was Vice-President of the same institution from 1899 until her death on January 11, 1907.

Mrs. McCall was born in London, England, October 26, 1824, to Charles Richard Basden Raymond and Margaret Priscilla Widenham Raymond. In December 1834 they set sail from London to arrive 10 weeks later in New Orleans. They came up the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers to Peoria. Her parents were scholarly and cultured. They taught their children literature, mathematics, history, and music. In Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois by Newton Bateman, 1908, she is described as “systematic, orderly, thorough and even executive at an age when most children find greatest solace in the companionship of their dolls, and in addition to these solid traits she was a musician of merit, possessing an excellent voice.”

In Peoria County, Illinois, on June 10, 1845, she married James Harvey McCall. They had four daughters, Margaret Louisa, Grace Caroline, Josephine Elizabeth, and Agnes. James McCall had operated a saw mill and grist mill in Peoria. In 1862 they moved to Canton, Illinois, where James had purchased a distillery. Mr. McCall became one of the founders of the First National Bank, of which he was President for the remainder of his life.

During the fall of 1872 James McCall went to California and became interested in the mining business. He kept his family posted on his travels, business, and health. While all reports seemed positive, in 1873 Mrs. McCall received word James had died.

Louisa McCall continued her husband’s business affairs. According to the newspaper account of Louisa McCall’s death from the Canton Daily Register, Mrs. McCall was instrumental in following through with a lawsuit involving her husband’s estate. Mr. McCall had sued his old partner in California and won the case. Although $35,000 was to be paid to James, upon James McCall’s death, the partner instead brought in a “writ of error” suit. The suit was eventually settled in Louisa McCall’s favor. Because of her large holdings she was later elected as a director at the First National Bank in 1877.

Louisa McCall died on January 11, 1907, of ill health. She had suffered from pneumonia in 1905 and never quite recovered. In addition to her position at the bank, Mrs. McCall was president of the Canton Aid Society for 25 years and had also contributed to many local organizations. She was known for her generosity as well as her great executive ability and keen business acumen.

Bibliography:

Bateman, Newton. Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois and History of Fulton County. Chicago: Munsell Publishing, 1908.

Contributing Library:

Parlin-Ingersoll Library, Canton, Illinois

Mahala Phelps (1845-1932), librarian

Miss Mahala Phelps |

|

Macomb Library Macomb Library

(Carnegie building) [top],

Miss Phelps [rt],

Edith Whitson Trail, member original library board [lt]

|

|

Mahala Phelps served the Macomb community as a librarian for almost fifty years. During her half-century in the Macomb library, she influenced the reading materials for the young people of the community and supported their education.

Miss Phelps was born in Macomb in 1845 and was a life-long resident of the city. She began her career as a teacher. In 1881, community members established a public library. At age 36, Miss Phelps became the librarian, a role which she would continue for the next half-century.

The first library opened in 1882 in a back room over a jewelry store on the south side of the Macomb square. The library owned a few hundred books and was open just 2 days each week. In 1883, the library moved to an upstairs room in City Hall.

The generosity of Andrew Carnegie made it possible for the library to construct its own building. The Carnegie building opened on South Lafayette in 1904. The Macomb City Library still (1998) occupies the building. (An addition to the north side expands the original building.) Prior to the move in 1904, Miss Phelps had devised a cataloging system for the books. When the library moved to the new building, Miss Margaret Dunbar, librarian of the Western State Teachers College (now Western Illinois University), assisted in migrating the cataloging system to a standard system.

Miss Phelps continued as librarian until about 1928. Even in retirement, she maintained an active interest in the institution. Miss Phelps took great care in choosing the books available on the library shelves. During the early days, she read each book and only those books she approved were made available in the library. She paid particular attention to young readers and assisted many school children with their projects. Her influence was felt over several generations of Macomb residents. |

Bibliography

- “Miss Phelps Funeral on Wednesday: Gave Life time of Service at Macomb Public Library”, Macomb Daily Journal, Macomb, IL. Oct. 18, 1932.

- Crabb, Richard. “Macomb Library to Celebrate 48 Years of Service During the Coming Week”, Peoria Star, Peoria, IL. Apr. 6, 1930.

- Hallwas, John E. (1990) “Women at Work”, in Macomb: A Pictorial History, G. Bradley Publishing, Inc., St. Louis, MO.

Contributing Library:

Macomb Public Library, Macomb, Illinois

Aunt Josie Westfall (1873-1941)

McDonough County Orphanage & Macomb City Judge

|

|

In 1911, Macomb had no public facility for the care of orphaned children. Some children were housed at the County Poor Farm, but the place was really not suitable for children. Limited other private facilities were available in the community. When two orphans became the focus of the community’s concern, Josie Westfall took on the task of caring for them. Within her life time, Josie would become the protector of hundreds of the community’s orphans.

“Aunt Josie” Westfall was born in 1873 in Macomb, Illinois. She did not marry and worked as a dressmaker. Josie began her career as “mother” by taking just 2 children into her home in 1911. Before a single year had passed, she was providing a home for 19 children. The county board of supervisors agreed to supply $25 per month to assist Josie in the children’s care.

In 1913, an Orphanage Board was appointed. The County purchased a 12-room house at 415 N. Madison Street in Macomb. An addition was soon added to the home, as the number of children grew to 67. Although the funding was increased, money was always in short supply.

In 1914, Josie ran for the position of Macomb City Judge and planned to donate her salary to the orphanage. She was elected by a large margin. Josie received a total of 839 votes to defeat her closest opponent’s total of 577. Her opponent contested the race in McDonough County court on the grounds that the election was not legal. Although the Illinois Women’s Suffrage Act was passed in 1913, the suit claimed the Act did not authorize ladies to vote in that judicial election. Josie’s opponent had received 430 votes from men to Josie’s 409 votes. The County court found in favor of Josie and women’s right to vote, but the Illinois Supreme Court reversed the decision. It would be 1920 before the 19th Amendment was passed. An interesting side note is that one of the lawyers representing Josie’s opponent was a woman.

Josie’s goal of serving the area children continued without the funds from a judicial position. She enlisted the assistance of area organizations. The community responded with clothing, food, medical services, and Christmas presents.

During the 1920s, the existing orphanage building became inadequate and funds were collected for a new building. The community responded with money, building materials, and furnishings. One of the more unusual donations came from the Stevens family, owners of the Stevens’ hotel in Chicago. They donated over 12 dozen new dishes. The children moved into the new building on East Jefferson Street in 1933.

During her career of thirty years as an orphanage matron, Josie provided guidance, food, shelter and care for over 500 children. She was not paid for her services, although she was provided with a place to live.

In 1940, an illness forced Josie to retire from her work. She died in June 1941 at the age of sixty-seven. The orphanage building was occupied by the Salvation Army and later sold as an apartment building. |

Bibliography

- Macomb Heritage Days Souvenir Book. 1982.

- Hallwas, John E. (1990) “Women at Work”, in Macomb: A Pictorial History, G. Bradley Publishing, Inc., St. Louis, MO.

- Jani, Shanti (ca. 1985) “Aunt Josie” reprinted in Macomb Heritage Days Souvenir Book. 1985.

- Nichols, Katherine. She sheltered the children: Westfall opened her heart – and her doors – to those in need. Macomb Daily Journal pp. 1E, 4E, July 28, 1996.

- Scott, Judge Keith F. “McDonough Bar History Described”, Macomb Daily Journal, Macomb, IL. May 6, 1976.

Contributing Library:

Macomb Public Library, Macomb, Illinois

Holmes Hospital, Macomb, Illinois

Phelps Hospital, Macomb, Illinois

Caroline Grote (left) & Anna H. McKee, Augusta, Illinois, June 5, 1894

Caroline Grote (left) & Anna H. McKee, Augusta, Illinois, June 5, 1894 Campus of Western Illinois University. Monroe Hall (renamed Grote Hall) is on the right. Sherman Hall, the first building on campus, is on the left

Campus of Western Illinois University. Monroe Hall (renamed Grote Hall) is on the right. Sherman Hall, the first building on campus, is on the left Monroe Hall, Western Illinois University

Monroe Hall, Western Illinois University Monroe Hall, Western Illinois University

Monroe Hall, Western Illinois University Caroline Grote

Caroline Grote

Photo of First National Bank of Canton, Illinois

Photo of First National Bank of Canton, Illinois

Macomb Library

Macomb Library

Josie & the children (

Josie & the children (

Autograph of Peter Cartwright, May 24, 1853

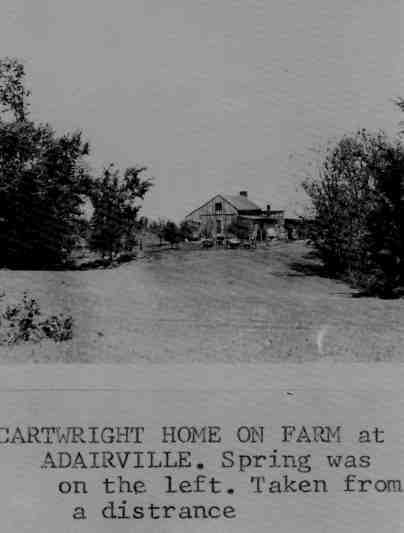

Autograph of Peter Cartwright, May 24, 1853 Picture of Homestead of Peter and Frances Cartwright, 1872

Picture of Homestead of Peter and Frances Cartwright, 1872

Peter’s Bible–inscription with description and first page, pg. 1

Peter’s Bible–inscription with description and first page, pg. 1 Peter’s Bible–with article of grandson donating Bible to Peter Cartwright UMC

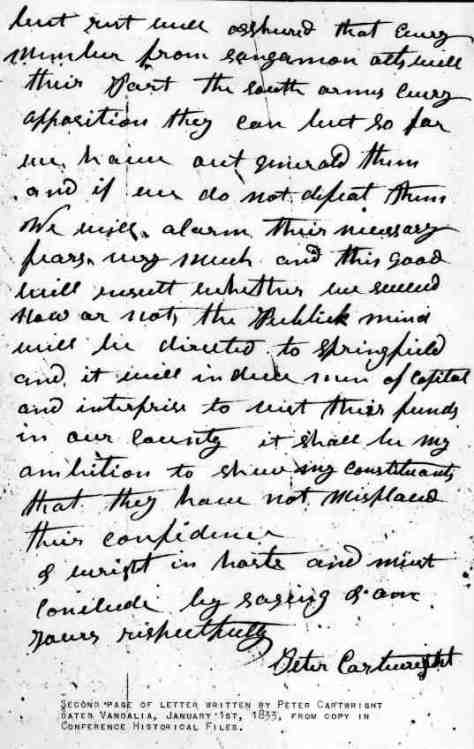

Peter’s Bible–with article of grandson donating Bible to Peter Cartwright UMC Letter written by Peter Cartwright, January 1, 1833, pg. 2

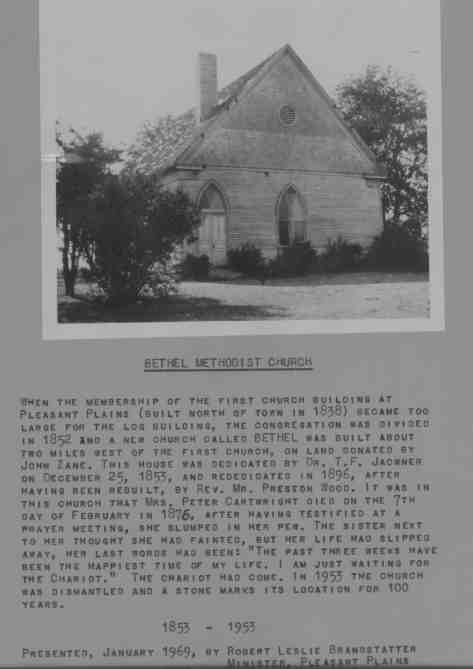

Letter written by Peter Cartwright, January 1, 1833, pg. 2 Bethel Methodist Church, telling about Frances Cartwright, Peter’s wife, dying in the church, see attachment

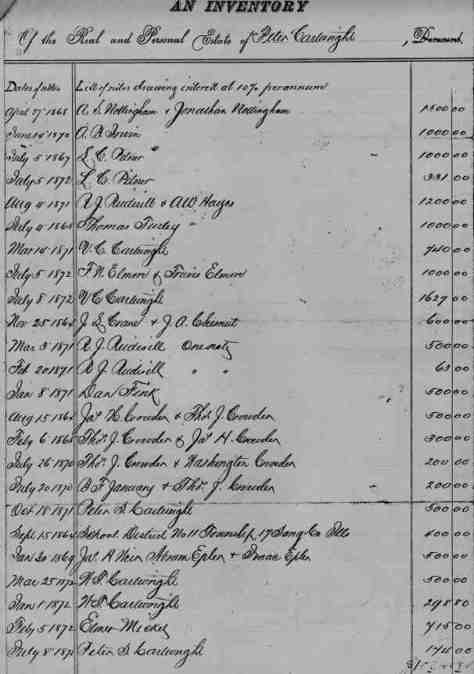

Bethel Methodist Church, telling about Frances Cartwright, Peter’s wife, dying in the church, see attachment Personal Estate Inventory, pg. 2

Personal Estate Inventory, pg. 2 Personal Estate Inventory, pg. 3

Personal Estate Inventory, pg. 3 Personal Estate Inventory, pg. 4

Personal Estate Inventory, pg. 4 Letter about Peter Cartwright’s parents, Feb. 14, 1956

Letter about Peter Cartwright’s parents, Feb. 14, 1956 Bethel Church Pulpit, 1853-1953

Bethel Church Pulpit, 1853-1953 Peter Cartwright, His Chair 1869, given by the Governor of Illinois

Peter Cartwright, His Chair 1869, given by the Governor of Illinois Chair owned by Peter Cartwright, 1785-1872. Ottoman at foot of chair is a reproduction of needlepoint work done by Frances Cartwright, wife of Peter. The original needlepoint has been framed (see below).

Chair owned by Peter Cartwright, 1785-1872. Ottoman at foot of chair is a reproduction of needlepoint work done by Frances Cartwright, wife of Peter. The original needlepoint has been framed (see below). Original needlepoint by Frances Cartwright

Original needlepoint by Frances Cartwright Peter Cartwright’s Desk

Peter Cartwright’s Desk Portraits of Peter and Frances Carthwright and pictures of their homestead. (Printed in 1916 issue of Pleasant Plains Press Newspaper)

Portraits of Peter and Frances Carthwright and pictures of their homestead. (Printed in 1916 issue of Pleasant Plains Press Newspaper) Bethel Church pulpit furniture

Bethel Church pulpit furniture Shelf made by Peter Cartwright from wood on his farm

Shelf made by Peter Cartwright from wood on his farm Cabinet from the Bethel Church

Cabinet from the Bethel Church Pew from the Bethel Church (Pew on which Frances Cartwright died)

Pew from the Bethel Church (Pew on which Frances Cartwright died) Dress worn by Frances Cartwright

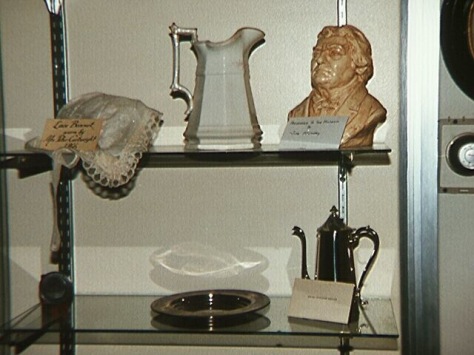

Dress worn by Frances Cartwright Lace Bonnet worn by Frances Cartwright (top) and Communion Service (bottom)

Lace Bonnet worn by Frances Cartwright (top) and Communion Service (bottom) 2 walking canes made by Peter Cartwright (letter dated 1849) one or Lucinda Capps and the other made out of barnwood from his farm.

2 walking canes made by Peter Cartwright (letter dated 1849) one or Lucinda Capps and the other made out of barnwood from his farm. Sette from the Bethel Church on which Frances Carwright was laid out after dying.

Sette from the Bethel Church on which Frances Carwright was laid out after dying. Interior of the present Peter Cartwright United Methodist Church, Pleasant Plains, Illinois

Interior of the present Peter Cartwright United Methodist Church, Pleasant Plains, Illinois Exterior of the present Peter Cartwright United Methodist Church, Pleasant Plains, Illinois

Exterior of the present Peter Cartwright United Methodist Church, Pleasant Plains, Illinois

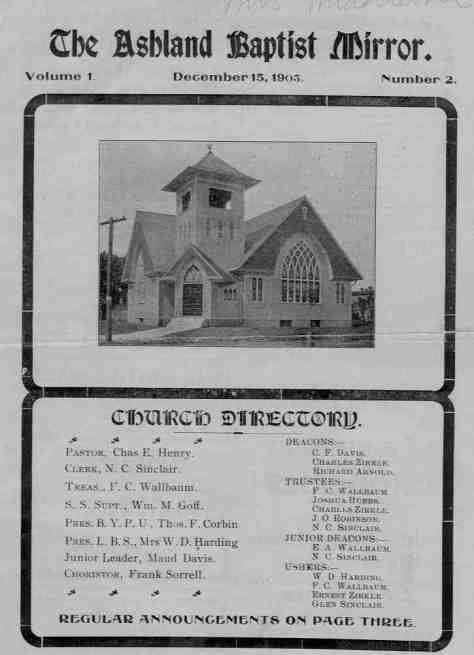

The Ashland Baptist Mirror, published semi-monthly in the interest of the Ashland Baptist Church, Charles E. Henry, Editor. Associates Wm. Goff–Young People, Mrs. J.H. Hubbs–“Chips”, Subscription price per year, 50 cents in advance. 1905

The Ashland Baptist Mirror, published semi-monthly in the interest of the Ashland Baptist Church, Charles E. Henry, Editor. Associates Wm. Goff–Young People, Mrs. J.H. Hubbs–“Chips”, Subscription price per year, 50 cents in advance. 1905 “Our Young People” by Wm. M. Goff, from the Ashland Baptist Mirror

“Our Young People” by Wm. M. Goff, from the Ashland Baptist Mirror Children of the Ashland Baptist Church

Children of the Ashland Baptist Church

L. Ickes to Miss Vittum

L. Ickes to Miss Vittum

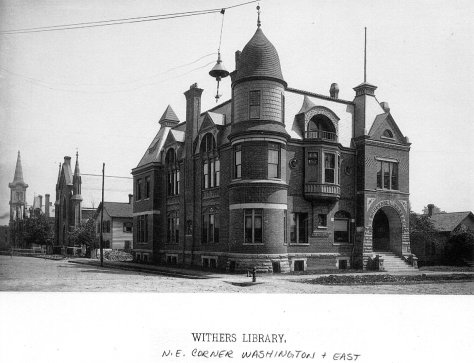

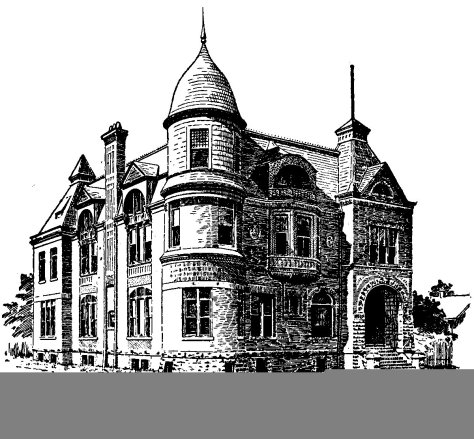

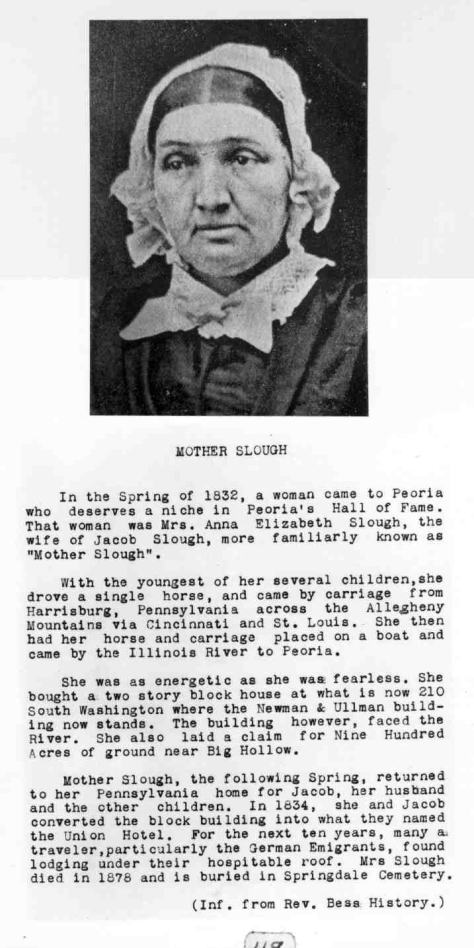

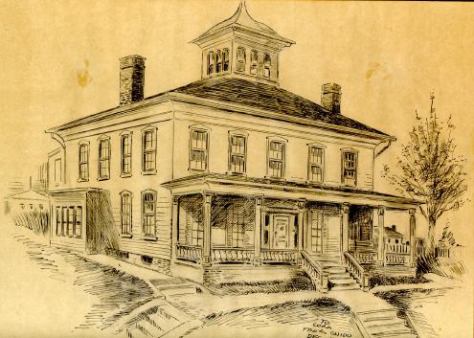

Sarah Withers

Sarah Withers